Hamilton Students Weigh Their Waste — and Their Actions

Bon Appétit Senior Fellow Nicole Tocco and Real Food Hamilton leaders Heather Krieger and Victoria Blumenfeld prepare to make food waste visible

Heather hangs up a sign as part of the Weigh the Waste Campaign

A group of Hamilton College students in Clinton, NY, noticed that a lot of food was being left on students’ plates at the end of meals. Led by Real Food Hamilton, the school’s Real Food Challenge (RFC) chapter, they set out to raise awareness among their peers about how much they waste and why it matters.

Bon Appétit chefs are proud to work with Real Food Challenge groups around the country to maximize the amount of “real food” on campus, which the RFC defines as food that is humane, ecologically sound, fair, or local. I meet a lot of inspiring students in my role as a Fellow for the Bon Appétit Management Company Foundation, but the Real Food Hamilton leaders Heather Krieger ’14 and Morgan Osborn ’14 stood out even in that crowd. Their passion for sustainable ingredients and for effecting change through purchasing is only the beginning. Heather and Morgan also recognized that many of the ingredients that qualify as “real food” cost more — but instead of trying to increase Bon Appétit’s budget for food on campus, they thought about opportunities to reduce waste, address environmental problems, and lower costs through waste reduction.

The Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that 40% of food goes uneaten in the United States. That much wasted food means the equivalent of $165 billion every year is going straight to a landfill, compost pile, or rotting in the fields. It also means that 25 percent of the fresh water America uses ends up going to waste — in a time of ongoing drought. Through cooking from scratch and batch cooking, Bon Appétit teams do keep waste at a minimum in our kitchens, and through an increasing number of cafes donating leftovers through food recovery programs, we’re helping to get food to hungry people in the communities that we serve. But in between those two steps, a lot of food left on the plates of our guests does get wasted at the end of their meal.

Fighting food waste is a simple idea with major payoffs: savings in time, money, and energy, and a lower carbon footprint. The chefs save money by wasting fewer ingredients and the time and energy spent cooking food that wasn’t eaten. Organic matter stays out of landfills (where it generates methane, a powerful greenhouse gas) or compost piles (where it is being transformed into a useful end product –soil! – but is still unnecessary waste and generates carbon dioxide, another key greenhouse gas).

At Hamilton College, financial savings resulting from less wasted food can be used to purchase more “real food,” such as Fair Trade bananas, meat from small, local farms or USDA Organic produce, which can cost more. So, a few months ago, I was thrilled to join those Real Food Hamilton students as they led a Weigh the Waste campaign with support from Bon Appétit General Manager Patrick Raynard and Executive Chef Derek Roy. During lunch, I stood with students near the tray return at Commons Dining Hall, asking diners to scrape their waste into three containers: edible food, inedible food such as banana peels, and disposable items such as paper napkins and cups.

Disrupting routine is a powerful thing. Students were visibly confused as they tried to figure out why we were standing between them and the dish return area (and hence between them and their next class or soccer practice). We weren’t there to judge or lecture, but its uncomfortable to have people call attention to waste you’ve created. As our words and the signs around us about food waste registered, I saw many sheepish looks of those seeing the waste on their plates with new eyes.

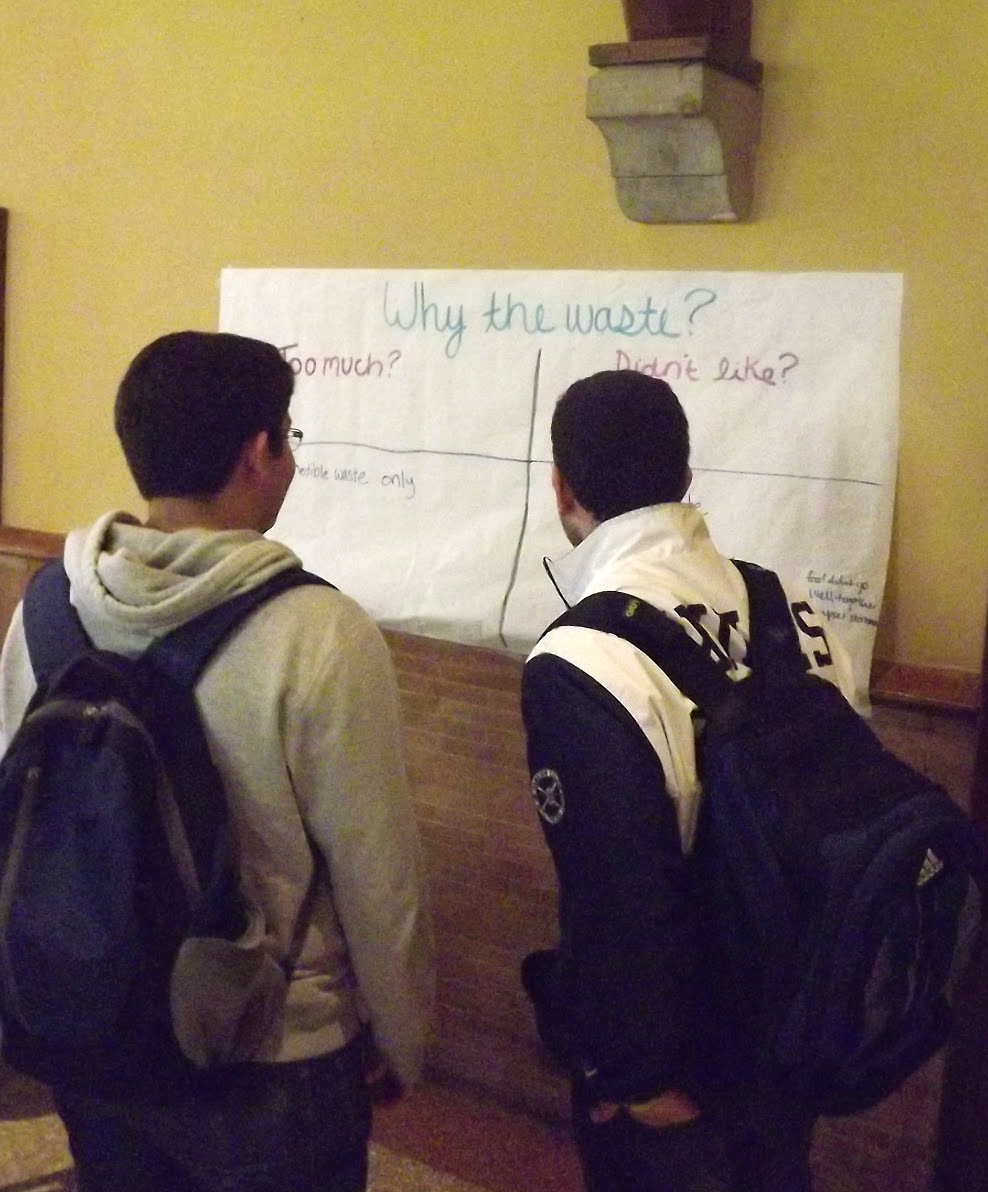

Students “weigh in”

Then it was time to scrape. We asked students to scrape their waste into separate containers depending on whether it was edible or inedible waste. In other words, was it a banana peel or a too-big helping of roasted root vegetables? And then, we asked each person the reason for their waste. Was the waste on their plate unavoidable (inedible bits), was it a disposable cup or napkin, or was it edible food that they had either taken too much of, or just didn’t like?

On the surface it seems like a simple question, but it went a long way in changing the way the 264 people we spoke to that day look at their plates. Asking that question helped us each think of the waste on our plates as something that could be avoided tomorrow, if we just take a lesson away from it today.

At the end of the first campaign, we had collected more than 50 pounds of edible food waste: ten times the amount of non-edible food waste. Some of the feedback (such as a premade salad with too much dressing for many students’ taste) was passed onto the chefs, and some (like the many students who reported taking more food than they had time or appetite to eat) we can only hope will influence their behavior differently in the future.

Heather and Morgan are trying to understand the system and take an active role in changing it. The more people we have like that, the more transparent and sustainable our food system will become. But it all starts with smart, passionate, and engaged leaders. At Hamilton College, the Bon Appétit team supports them. That support encourages them, and helps them to reach their peers with events like these and spread their eagerness for change. And maybe even, as Fedele Bauccio encouraged graduates of Albion College in May 2014, to eat like they give a damn.