Will New England really be New England without cranberry bogs?

- by tribe

A team of research scientists working for multiple Federal agencies including Defense, Agriculture, Commerce and others released a report on June 16 that got curiously little media attention. Draped in the dry language of government reports, Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States paints a dramatic picture of what our agricultural system could become if average temperatures rise more than two degrees Celsius over the next half century. To wit:

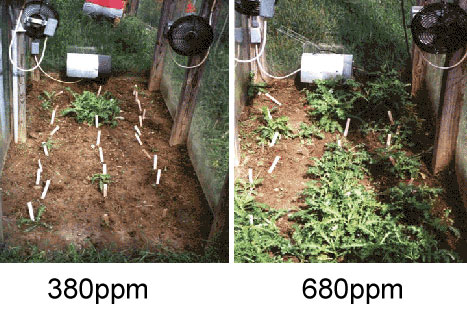

1. It is a myth that higher temperatures will make it easier to grow crops and livestock in regions that are now cold. While many crops positively respond to higher levels of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, they reported, higher levels of warming affect growth and yields negatively. Why? With higher temperatures also come “extreme events” such as heavy downpours and droughts which reduce yields overall and kill some plantings altogether. Higher temperatures also increase weed growth, plant diseases, and insects, resulting in less crop yield and more need for pesticides. Weeds cause plants to need more water and farmers to need more labor (or chemicals or mechanical devices) to control weed growth. A mess all around. These pictures show that a higher concentration of CO2 [the very definition of global warming] will cause faster weed growth.

2. Higher temperatures will mean a longer growing season for crops that do well in the heat, such as cereal crops, but faster growth means there is less time for the grain itself to grow and mature, which will have a negative effect on yields. Higher carbon dioxide levels generally cause plants to grow larger. For some crops, this isn’t necessarily a good thing because they are often less nutritious.

3. Fruits that require long winter chilling periods will decline. Many varieties of fruits (think apples and berries) require between 400 and 1,800 cumulative hours below 45°F each winter to produce abundant yields the following summer and fall. Under higher greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, winter temperatures in many important fruit-producing regions such as the Northeast will be too consistently warm to meet these requirements. Cranberries have a particularly “high chilling” requirement, and there are no known low-chill varieties. The report concluded that “by the middle of this century, it is unlikely that [

4. Like human beings, cows, pigs, and poultry are warm-blooded animals that are sensitive to heat. Studies show that the negative effects of hotter summers will out-weigh the positive effects of warmer winters in terms of production efficiency. The more the U.S.climate warms, the more production will fall.

What to make of all of this? Growers aren’t stupid. They are likely to figure out different things to grow. But adaptation costs money and the cost of food will certainly rise as a result. Our palates will need to change (they always do) and flavors and traditions will be lost. That may not sound catastrophic, but how much loss of biological varieties can our habitats sustain? Are more pesticides and more water usage the direction we want to go in to raise the same amount of food (or more)? Aren’t we trying to stress animals less, not more?

– Helene S. York, Director, Bon Appetit Management Company Foundation