Where There’s a Mill, There’s a Way: Reviving Maine’s Grain Economy

The exterior of the Maine Grains mill. The dustbins are equipped with lasers to detect sparks and will auto shut down to prevent explosions.

You would never guess that an old jail would make for an ideal site for a grain mill.

But the abandoned Skowhegan prison has proven to be the perfect place for Maine Grains, a certified organic mill in Central Maine — and a new addition to Bon Appétit’s Farm to Fork roster. The jail’s many floors make it easier to vertically integrate all steps of the milling process. Tubes carry grain through the floors and ceilings, moving from attic storage, to dehulling machines, to cleaning tubes, to the milling stone. The easily cleaned concrete walls dampen the sound of noisy machinery. Even the prison’s old kitchen has been turned into a farm-to-table café featuring scrumptious local grains. The space perfectly embodies cofounder Amber Lambke’s goal when she started Maine Grains: revitalizing Central Maine economies through existing community assets.

Milling about

I visited Maine Grains a few months ago while enrolling local vendors into the Farm to Fork program for the new Bon Appétit cafés at Colby College in Waterville, ME. As a “mill city” native (I’m from Minneapolis), I was anxious to see a certified organic mill that served local producers. Small local mills, like many intermediary food processors, are a rare breed.

In fact it was this very lack of local mills that inspired Amber to open Maine Grains. Amber had cofounded a nonprofit called the Maine Grains Alliance, which hosts an annual KNEADING Conference. This coalition of businesses and nonprofits seek to revive regional grain economies as a form of rural development. Through their meetings and research, the Maine Grain Alliance kept pointing to a dire need for more local processing facilities, especially in central Maine. But no one had proposed to actually start one — until Amber thought, Why not me?

Maine Grains cofounder Amber Lambke shows how grains flow between floors in metal tubes

Before founding the Maine Grains Alliance, Amber had no agriculture or food processing experience. She was a communications major and speech-language pathologist: a community organizer interested in rural development. As a member of a Skowhegan development committee, she noticed that the conversation always centered around attracting businesses to set up shop in Skowhegan. Amber was interested in building wealth from within the community, by the community.

It took Amber and her business partner Michael Scholz five years to grow the Maine Grains mill from an idea to a brick-and-mortar facility. They opened in 2012 with only two supplying farms. “We started taking risks and inspired others to join us,” Amber said. Now they work with over 24 certified organic growers, 90% of which are from Maine. Last year they processed 360 tons of grain, and this year they are on track to do 700 tons and growing.

“One ton of milled flour represents about one acre of grain,” Amber explained, “and while 700 acres of organic grain may seem like a lot, that’s nothing compared to all the acres of conventional. We process in a year what a large miller does in a day. And organic grain still only represents one-tenth of 1 percent of all grain produced in the U.S.”

Amber and the Austrian mill stone

So although Maine Grain’s growth is impressive, Lambke is committed to going farther to build Maine’s capacity to process more organic grain. She recently received a USDA grant to buy two new German dehulling machines. These large-barreled contraptions will increase her ability to break down grains with tough hulls and chaffs such as spelt and other heritage grains, and possibly other products like sunflower seeds.

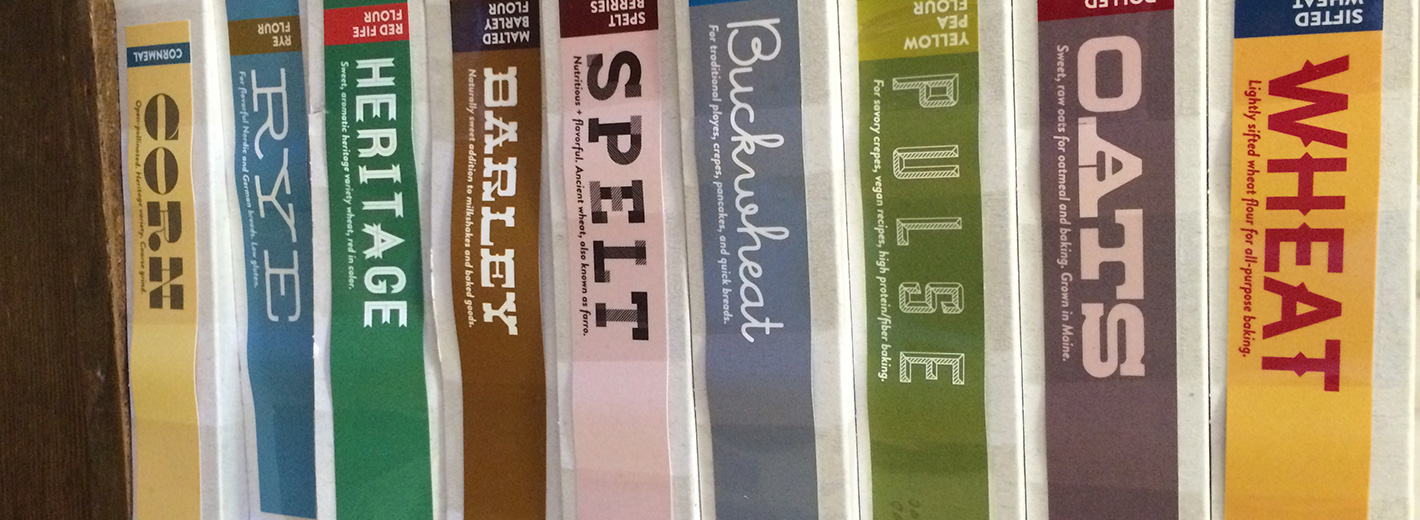

Maine Grains currently processes a wide variety of cereals, including wheat, oats, buckwheat, spelt, rye, corn, red fife wheat, barley and yellow peas. The facility’s centerpiece is a wood-covered Austrian mill that grinds grains between two 4-foot-wide millstones. Amber was attracted to the simple technology, which mills more slowly to keep the grain cool and maintain more nutrients. The wooden design also makes for quieter production.

Maine Grains shares Bon Appétit’s commitment to the fresh small-batch creations. They mill everything to order. Unlike other flours, their products have a shorter six-month shelf life: Lambke believes grains should be treated like produce, best enjoyed as close as possible to when they were harvested for optimum flavor and nutrition.

Colby students should feel proud to be enjoying such a high-quality product in their baked goods, from a business that’s making a real impact in the central Maine food system.