No Free Lunch: What “Gestation-Crate-Free” Pork Actually Means

I’ve been writing purchasing policies for Bon Appetit Management Company for over a decade, and I’ve learned some hard lessons along the way. One thing I know for sure: We have to be precise in our language.

We’re famous for giving our chefs great freedom to create their menus, as long as they follow our specific purchasing standards. When we’re asking more than 1,000 chefs in 32 states to follow a policy, leaving room for interpretation can be a recipe for confusion. This is why we have a specific definition for “local” and which seafood we call “sustainable.”

What I learned made my blood boil and pushed me to a not-so-gracious place in a few meetings. It also sent me on a pork-searching odyssey from the cornfields of Iowa to the back roads of rural Pennsylvania, and cost Bon Appétit a lot more money than expected … but ultimately got us a product we’re proud to serve.

I thought I’d been very clear when drafting our 2012 policy on the humane treatment of breeding sows. “Gestation crate free” meant no use of gestation crates. Pretty straightforward, right? I’d spoken to our largest pork supplier, I’d seen this term in their public announcements, and I talked to our partners at the Humane Society of the United States. We were all saying the same thing: gestation crate free.

As I found out, however, we weren’t all talking about the same practices.

What I learned made my blood boil and pushed me to a not-so-gracious place in a few meetings. It also sent me on a pork-searching odyssey from the cornfields of Iowa to the back roads of rural Pennsylvania, and cost Bon Appétit a lot more money than expected … but ultimately got us a product we’re proud to serve.

Sow What?

First, a little background. For the last few decades, most of the breeding pigs in the U.S. (6 million animals currently) have spent almost their entire lives in small metal crates. These highly intelligent, social, and sensitive 400- to 600-pound animals are confined to metal cages about 2 feet wide, set on slatted concrete floors, that are too small for them to turn around in or take more than a step forward or backward. They’re constantly kept pregnant (“gestation” refers to pregnancy): they have a litter every five months. Their pregnancies last 3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days, plus or minus two days; once they give birth, they spend two to four weeks with the piglets in a “farrowing crate” (which they also can’t turn around in) and then it’s back to the gestation crate to be artificially inseminated again. Repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat until their litter size drops, then it’s making bacon time.

Me and Barry Estabrook, author of Pig Tales, preparing to go inside a Clemens hog barn in Pennsylvania

As Barry Estabrook explains in his award-winning 2015 book Pig Tales, producers didn’t invent gestation crates out of sadism: once hog farms scaled up to thousands of animals and only a few workers per facility, putting sows in crates seemed like a practical, efficient way to make sure each sow stayed pregnant, got enough food, wouldn’t be bullied, and any illnesses would be seen and treated.

Still, it’s a horrible solution to a problem that was created by industrial production. That’s why in February 2012 we pledged to phase out pork raised using gestation crates by 2015. Bon Appétit Management Company was the first food service company to make this commitment, and we set the most aggressive deadline of any that have followed our lead.

Back when we made that promise, I had no idea where we were going to find 2.9 million pounds of gestation-crate-free pork. Producers weren’t exactly eager to get rid of gestation crates. We got called “cheese-eating surrender monkeys” and a “water-carrier” for the HSUS by an industry lobbyist in a Pork Network op-ed who urged the pork industry to stand behind its use of what he called “maternity pens.”

Although three big pork producers had by then promised to phase out gestation crates at all company-owned facilities, that was just a small fraction of their supply and their deadline for doing so was 2017 or later. (Overhauling buildings filled with rows upon rows of metal cages set into concrete into group housing pens is neither a fast nor cheap undertaking.) So I was thrilled when our existing supplier promised me a supply of gestation-crate-free pork.

How Do You Define “Free”?

We started with bacon, since bacon accounts for the largest percentage (one-third) of the pork we buy. A few months in, I heard that our pork supplier had suggested to our purchasing arm that we use the phrase “group housing” instead of “gestation crate free.” I went straight to the top, emailing the chief sustainability officer to ask what exactly they meant.

To his credit, he responded straightforwardly. He said the phrase gestation “crate free” was not 100% accurate because all producers use gestation stalls for the first 5 or 6 weeks in order to confirm pregnancy. He sent me a YouTube video that described the timing from crate to group housing.

Later, after I picked my jaw up off my desk and put the pieces of the rest of my exploded head back together, I called my friend Josh Balk, HSUS’s senior food policy director, in righteous indignation.

“Yeah, we know,” he sighed. “While it’s still better than a lifetime of confinement as they previously had, it’s still a problem.”

But it just didn’t sit right with us for many reasons. From an animal-welfare standpoint, that was still a couple of months per year spent confined in a cruel and inhumane system. Not only wasn’t it 100% accurate, it was more like 68% accurate (10-11 weeks in group housing out of a 16-week pregnancy). That kind of fudging is just not our style. We’re geeks when it comes to transparency and terminology: for example, we buy chicken “raised without routine nontherapeutic antibiotics” not “antibiotic-free chicken.”

A Pork in the Road

So we went looking for new pork. We do buy some truly gestation-crate-free pork around the country from Farm to Fork vendors including Pure Country Pork in Washington, Miller Livestock in Ohio, and Savannah River Farms in Georgia, but not only is there not enough of it to fill a 2.9-million-pound order, the price difference would kill us at that scale.

Ditto for the larger regional pork co-ops and companies, although I did meet with one in Iowa and tour their impressive outdoor hog farms. We just couldn’t make the numbers work for a companywide switch. Unlike consumer-facing companies like Chipotle and Whole Foods, we can’t charge whatever we want for our dishes. We have to work with our clients — universities and corporations — to set prices that are acceptable to thousands of college students and corporate employees who just want to grab lunch on campus.

Josh came to my rescue. “You know, there is ‘7-day pork’ out there,” he said. He told me about a large, privately owned Pennsylvania pork company called Clemens Food Group that was working with the New Bolton swine research facility at University of Pennsylvania to test out various humane approaches for its highest-end product line. Clemens had gotten its gestation-crate use down to just 3-10 days following insemination for its Farm Promise brand.

Holding a piglet at a Clemens farrowing facility

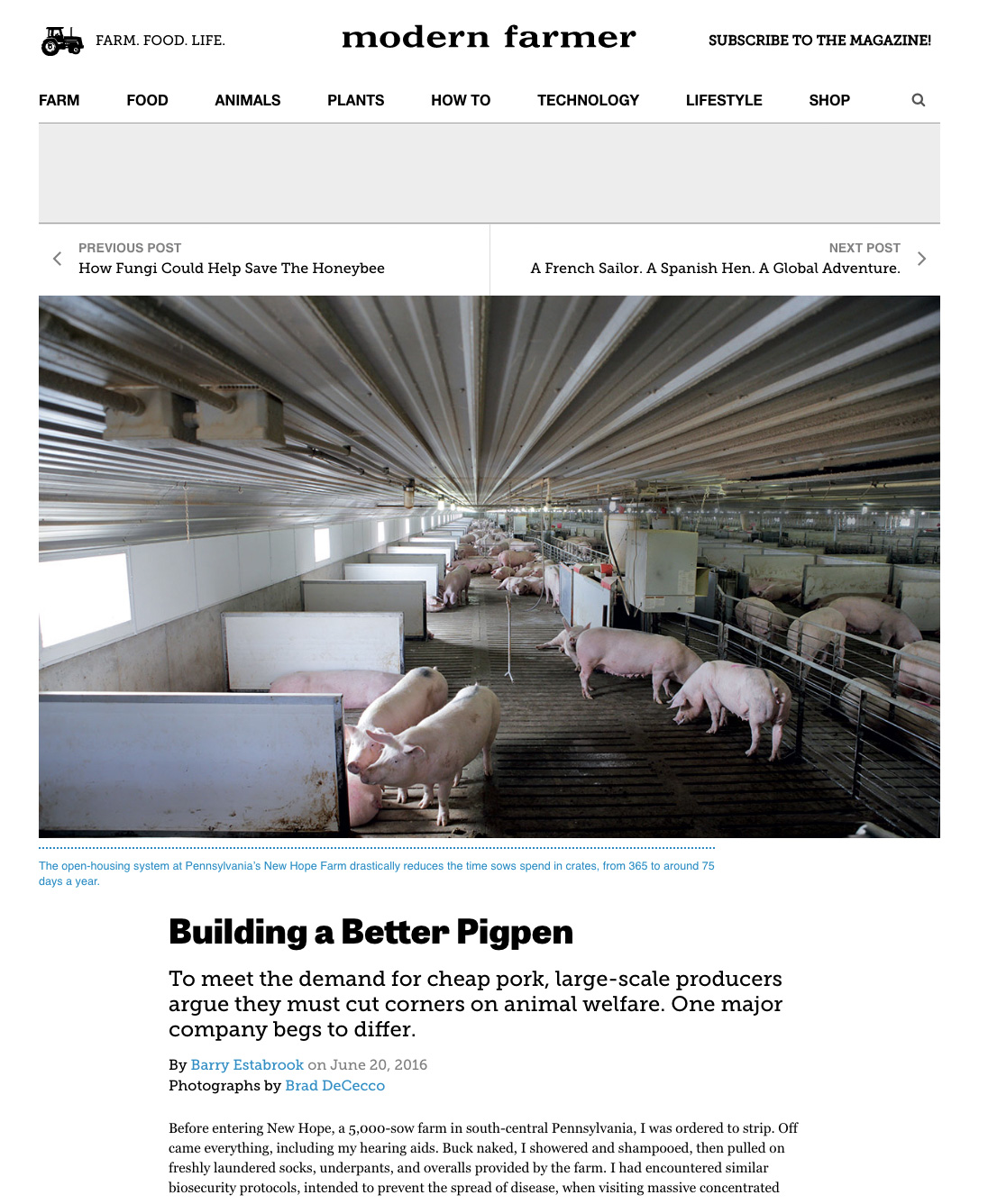

I contacted Clemens, explained what I’d heard and what I was looking for, and asked if I could tour the facilities that supplied the Farm Promise line. They said sure, without hesitation, which was a great sign. A few weeks later, I was seeing those facilities with my own eyes — having first showered and changed into an entirely new, sterile set of clothes (and underwear!). My host Bob Ruth, president of Clemens Food Group production division and manager of the Farm Promise program, showed me the few rows of gestation crates that remained in each massive barn, bordering the group pens. The sows have RFID tags that allow them to be fed and tracked individually even when they’re not in the individual stalls. Bob jumped over the railings into the group pens, and at his invitation I did too. We walked amongst these giant creatures as they nuzzled our hands and clothes.

“This is one way we can tell whether our workers are doing a good job,” Bob said. “The animals should feel relaxed around people.” And indeed, everyone I met on two full days of farm visits treated the sows and their piglets warmly and affectionately.

Bob explained that they still need to confine sows 5 to 7 days just before and after insemination because their hormonal changes can make them targets for the more aggressive sows in the open pen, and that’s when they’re most likely to miscarry. He said they were also working with the New Bolton Center to try out different farrowing-crate options that would give the sows more freedom. (I later got to tour New Bolton and see the progressive work they’re doing.)

I also learned, to my great excitement, all of the Farm Promise brand pork comes from animals that are never given antibiotics or ractopamine (a popular growth promoter that other countries have banned).

A Modern Farm with Nothing to Hide

All of this comes at a price premium, to be sure, but we decided the issue was important enough justify the price increase. Just in time for our end-of-2015 deadline, we signed a contract with Clemens and began the process of getting their products into our distribution system. And we reluctantly rewrote our website and marketing materials to say “our pork comes from sows raised in group housing” rather than “gestation-crate free” because well, we’re nerds and even Clemens’ industry-leading minimum isn’t the same as “free.”

We asked Barry Estabrook, that James Beard–award-winning author I mentioned above, whether he’d looked at Clemens when he was writing Pig Tales and knew about their gestation crate practices. He hadn’t, and he was intrigued. I invited him to come with me on a visit to Clemens and write about it. Clemens agreed, including allowing a photographer to return later. In a country where the meat industry has managed to get six states to pass ag-gag laws making it illegal to photograph or videotape industrial farms — and more would like to ban visitors — that openness once again sets this company apart.

Here’s Barry’s piece about our visit, which just came out in Modern Farmer. It’s been a long journey — I first shared our quest for gestation-crate-free pork back in this 2013 TEDxManhattan talk, How the Humane Sausage Gets Made! — but I feel extremely lucky that it’s ended in 2.9 million pounds of pork that we can feel good about.

Maisie Ganzler is Bon Appétit’s Chief Strategy and Brand Officer